[Source: @skeleton_claw]

Jupiter’s moons hide giant subsurface oceans – two upcoming missions are sending spacecraft to see if these moons could support life

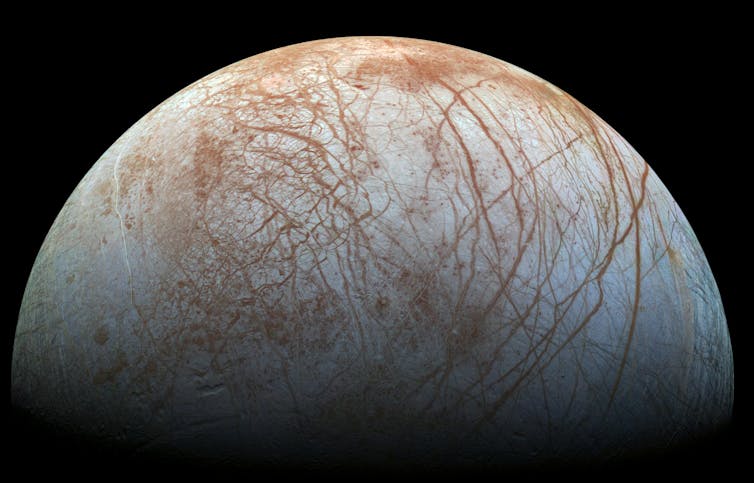

NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute, CC BY-SA

On April 13, 2023, the European Space Agency is scheduled to launch a rocket carrying a spacecraft destined for Jupiter. The Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer – or JUICE – will spend at least three years on Jupiter’s moons after it arrives in 2031. In October 2024, NASA is also planning to launch a robotic spacecraft named Europa Clipper to the Jovian moons, highlighting an increased interest in these distant, but fascinating, places in the solar system.

I’m a planetary scientist who studies the structure and evolution of solid planets and moons in the solar system.

There are many reasons my colleagues and I are looking forward to getting the data that JUICE and Europa Clipper will hopefully be sending back to Earth in the 2030s. But perhaps the most exciting information will have to do with water. Three of Jupiter’s moons – Europa, Ganymede and Callisto – are home to large, underground oceans of liquid water that could support life.

Meet Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto

Jupiter has dozens of moons. Four of them in particular are of interest to planetary scientists.

Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto are, like Earth’s Moon, relatively large, spherical complex worlds. Two previous NASA missions have sent spacecraft to orbit the Jupiter system and collected data on these moons. The Galileo mission orbited Jupiter from 1995 to 2003 and led to geological discoveries on all four large moons. The Juno mission is still orbiting Jupiter today and has provided scientists with an unprecedented view into Jupiter’s composition, structure and space environment.

These missions and other observations revealed that Io, the closest of the four to its host planet, is abuzz with geological activity, including lava lakes, volcanic eruptions and tectonically formed mountains. But it is not home to large amounts of water.

Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, in contrast, have icy landscapes. Europa’s surface is a frozen wonderland with a young but complex history, possibly including icy analogs of plate tectonics and volcanoes. Ganymede, the largest moon in the entire solar system, is bigger than Mercury and has its own magnetic field generated internally from a liquid metal core. Callisto appears somewhat inert compared to the others, but serves as a valuable time capsule of an ancient past that is no longer accessible on the youthful surfaces of Europa and Io.

Most exciting of all: Europa, Ganymede and Callisto all almost certainly possess underground oceans of liquid water.

Ocean worlds

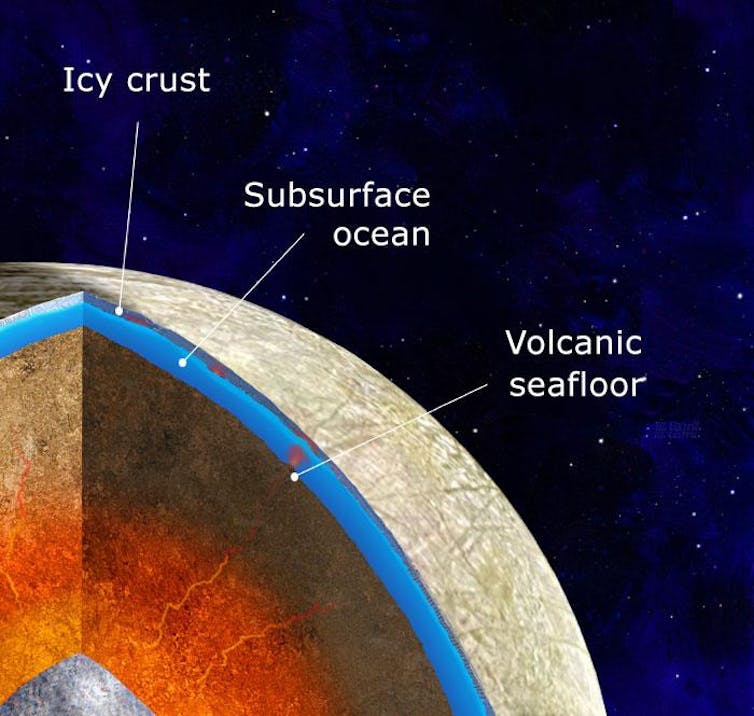

Europa, Ganymede and Callisto have chilly surfaces that are hundreds of degrees below zero. At these temperatures, ice behaves like solid rock.

But just like Earth, the deeper underground you go on these moons, the hotter it gets. Go down far enough and you eventually reach the temperature where ice melts into water. Exactly how far down this transition occurs on each of the moons is a subject of debate that scientists hope to resolve with JUICE and Europa Clipper. While the exact depths are still uncertain, scientists are confident that these oceans exist.

The best evidence of these oceans comes from Jupiter’s magnetic field. Saltwater is electrically conductive. So as these moons travel through Jupiter’s magnetic field, they generate a secondary, smaller magnetic field that signals to researchers the presence of an underground ocean. Using this technique, planetary scientists have been able to show that the three moons contain underground oceans. And these oceans are not small – Europa’s ocean alone might have more than double the water of all of Earth’s oceans combined.

An obvious and tantalizing next question is whether these oceans can support extraterrestrial life. Liquid water is an important piece of what makes for a habitable world, but far from the only requirement for life. Life also needs energy and certain chemical compounds in addition to water to flourish. Because these oceans are hidden beneath miles of solid ice, sunlight and photosynthesis are out. But it’s possible other sources could provide the needed ingredients.

On Europa, for example, the liquid water ocean overlays a rocky interior. That rocky seafloor could provide energy and chemicals through underwater volcanoes that could make Europa’s ocean habitable. But it is also possible that Europa’s ocean is a sterile, inhospitable place – scientists need more data to answer these questions.

Upcoming missions from ESA and NASA

JUICE and Europa Clipper are set up to give scientists game-changing information about the potential habitability of Jupiter’s moons. While both missions will gather data on multiple moons, JUICE will spend time orbiting and focusing on Ganymede, and Europa Clipper will make dozens of close flybys of Europa.

Both of the spacecraft will carry a suite of scientific instruments built specifically to investigate the oceans. Onboard radar will allow JUICE and Europa Clipper to probe into the moons’ outer layers of solid ice. Radar could reveal any small pockets of liquid water in the ice, or, in the case of Europa, which has a thinner outer ice layer than Ganymede and Callisto, hopefully detect the larger ocean.

Magnetometers will also be on both missions. These tools will give scientists the opportunity to study the secondary magnetic fields produced by the interaction of conductive oceans with Jupiter’s field in great detail and will hopefully give researchers clues to salinity and volumes of the oceans.

Scientists will also observe small variations in the moons’ gravitational pulls by tracking subtle movements in both spacecrafts’ orbits, which could help determine if Europa’s seafloor has volcanoes that provide the needed energy and chemistry for the ocean to support life.

Finally, both craft will carry a host of cameras and light sensors that will provide unprecedented images of the geology and composition of the moons’ icy surfaces.

Maybe one day, a spacecraft will be able to drill through the miles of solid ice on Europa, Ganymede or Callisto and explore oceans directly. Until then, observations from spacecraft like JUICE and Europa Clipper are scientists’ best bet for learning about these ocean worlds.

When Galileo discovered these moons in 1609, they were the first objects known to directly orbit another planet. Their discovery was the final nail in the coffin of the theory that Earth – and humanity – resides at the center of the universe. Maybe these worlds have another humbling surprise in store.

Mike Sori, Assistant Professor of Planetary Science, Purdue University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Drunk Genie [Comic]

[Source: @stbeals]

A Roach in the Terran Army [Short Sci-Fi Story]

“Urburburr Burrub, Officer, here to be emplaced with the 5th Human Exosolar Unit.”

I did my best to imitate a human salute like I had seen others give while standing in line, but my chitin simply does not flex as well as human dermal sheathing, nor do my shoulders join in the same way. The human with the tablet who was directing the queue of soldiers disembarking raised an eyebrow at my salute, so I suspected I had either done well enough to be respectable, or done poorly enough to be humorous. With humans, it might well be both.

Emily the Human: Fried Chicken [Comic]

[Source: @Butajape]

Bowser has seen the Internet… he knows what would happen next [Comic]

[Source: @Idiotoftheeast]

Year Zero [Comic]

[Source: @zipfreemancomics]

We’re Having a T-Shirt Sale, and Here’s a Pic of Us Wearing Some of Them

Just a quick post to let you know that we’re having a t-shirt sale! $16 per tee for the rest of the day, and the sale might be extended to tomorrow, but we never know.

Also, this is us! As you see, we’re real human beings! 😂

You can also use the search feature over at the t-shirt store to find what you are interested in. There are 1000s of designs on sale!

Please note that Geeks are Sexy might get a small commission from qualifying purchases done through our posts.

Torrents of Antarctic meltwater are slowing the currents that drive our vital ocean ‘overturning’ – and threaten its collapse

Matthew England, UNSW Sydney; Adele Morrison, Australian National University; Andy Hogg, Australian National University; Qian Li, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Steve Rintoul, CSIRO

Off the coast of Antarctica, trillions of tonnes of cold salty water sink to great depths. As the water sinks, it drives the deepest flows of the “overturning” circulation – a network of strong currents spanning the world’s oceans. The overturning circulation carries heat, carbon, oxygen and nutrients around the globe, and fundamentally influences climate, sea level and the productivity of marine ecosystems.

But there are worrying signs these currents are slowing down. They may even collapse. If this happens, it would deprive the deep ocean of oxygen, limit the return of nutrients back to the sea surface, and potentially cause further melt back of ice as water near the ice shelves warms in response. There would be major global ramifications for ocean ecosystems, climate, and sea-level rise.

Our new research, published today in the journal Nature, uses new ocean model projections to look at changes in the deep ocean out to the year 2050. Our projections show a slowing of the Antarctic overturning circulation and deep ocean warming over the next few decades. Physical measurements confirm these changes are already well underway.

Climate change is to blame. As Antarctica melts, more freshwater flows into the oceans. This disrupts the sinking of cold, salty, oxygen-rich water to the bottom of the ocean. From there this water normally spreads northwards to ventilate the far reaches of the deep Indian, Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. But that could all come to an end soon. In our lifetimes.

Why does this matter?

As part of this overturning, about 250 trillion tonnes of icy cold Antarctic surface water sinks to the ocean abyss each year. The sinking near Antarctica is balanced by upwelling at other latitudes. The resulting overturning circulation carries oxygen to the deep ocean and eventually returns nutrients to the sea surface, where they are available to support marine life.

If the Antarctic overturning slows down, nutrient-rich seawater will build up on the seafloor, five kilometres below the surface. These nutrients will be lost to marine ecosystems at or near the surface, damaging fisheries.

Changes in the overturning circulation could also mean more heat gets to the ice, particularly around West Antarctica, the area with the greatest rate of ice mass loss over the past few decades. This would accelerate global sea-level rise.

An overturning slowdown would also reduce the ocean’s ability to take up carbon dioxide, leaving more greenhouse gas emissions in the atmosphere. And more greenhouse gases means more warming, making matters worse.

Meltwater-induced weakening of the Antarctic overturning circulation could also shift tropical rainfall bands around a thousand kilometres to the north.

Put simply, a slowing or collapse of the overturning circulation would change our climate and marine environment in profound and potentially irreversible ways.

Signs of worrying change

The remote reaches of the oceans that surround Antarctica are some of the toughest regions to plan and undertake field campaigns. Voyages are long, weather can be brutal, and sea ice limits access for much of the year.

This means there are few measurements to track how the Antarctic margin is changing. But where sufficient data exist, we can see clear signs of increased transport of warm waters toward Antarctica, which in turn causes ice melt at key locations.

Indeed, the signs of melting around the edges of Antarctica are very clear, with increasingly large volumes of freshwater flowing into the ocean and making nearby waters less salty and therefore less dense. And that’s all that’s needed to slow the overturning circulation. Denser water sinks, lighter water does not.

How did we find this out?

Apart from sparse measurements, incomplete models have limited our understanding of ocean circulation around Antarctica.

For example, the latest set of global coupled model projections analysed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change exhibit biases in the region. This limits the ability of these models in projecting the future fate of the Antarctic overturning circulation.

To explore future changes, we took a high resolution global ocean model that realistically represents the formation and sinking of dense water near Antarctica.

We ran three different experiments, one where conditions remained unchanged from the 1990s; a second forced by projected changes in temperature and wind; and a third run also including projected changes in meltwater from Antarctica and Greenland.

In this way we could separate the effects of changes in winds and warming, from changes due to ice melt.

The findings were striking. The model projects the overturning circulation around Antarctica will slow by more than 40% over the next three decades, driven almost entirely by pulses of meltwater.

Over the same period, our modelling also predicts a 20% weakening of the famous North Atlantic overturning circulation which keeps Europe’s climate mild. Both changes would dramatically reduce the renewal and overturning of the ocean interior.

We’ve long known the North Atlantic overturning currents are vulnerable, with observations suggesting a slowdown is already well underway, and projections of a tipping point coming soon. Our results suggest Antarctica looks poised to match its northern hemisphere counterpart – and then some.

What next?

Much of the abyssal ocean has warmed in recent decades, with the most rapid trends detected near Antarctica, in a pattern very similar to our model simulations.

Our projections extend out only to 2050. Beyond 2050, in the absence of strong emissions reductions, the climate will continue to warm and the ice sheets will continue to melt. If so, we anticipate the Southern Ocean overturning will continue to slow to the end of the century and beyond.

The projected slowdown of Antarctic overturning is a direct response to input of freshwater from melting ice. Meltwater flows are directly linked to how much the planet warms, which in turn depends on the greenhouse gases we emit.

Our study shows continuing ice melt will not only raise sea-levels, but also change the massive overturning circulation currents which can drive further ice melt and hence more sea level rise, and damage climate and ecosystems worldwide. It’s yet another reason to address the climate crisis – and fast.

Matthew England, Scientia Professor and Deputy Director of the ARC Australian Centre for Excellence in Antarctic Science (ACEAS), UNSW Sydney; Adele Morrison, Research Fellow, Australian National University; Andy Hogg, Professor, Australian National University; Qian Li, , Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Steve Rintoul, CSIRO Fellow, CSIRO

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Egg Hunter [Comic]

[Source: @optipess]