[Source: @theimmortalgrind]

Paul Reubens Explains the Creation of Pee-Wee Herman in a 1981 Interview

Watch as actor and comedian Paul Reubens explains how he came up with his alter ego Pee-wee Herman in this 1981 interview on CNN.

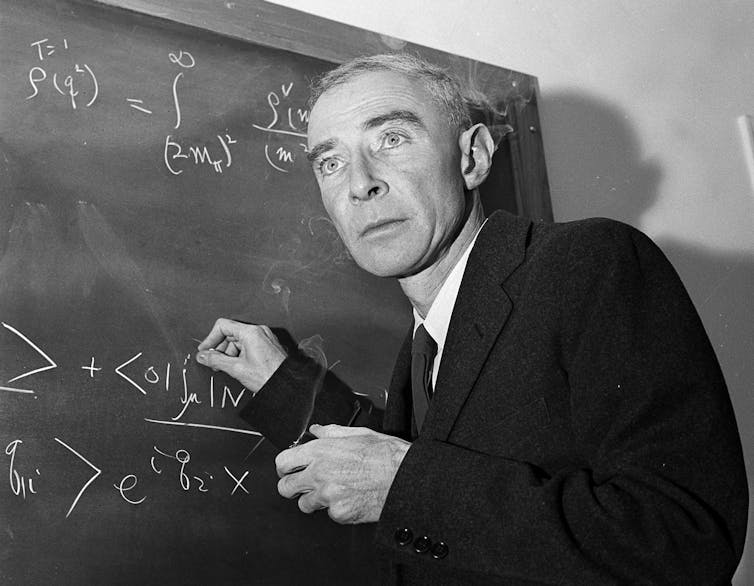

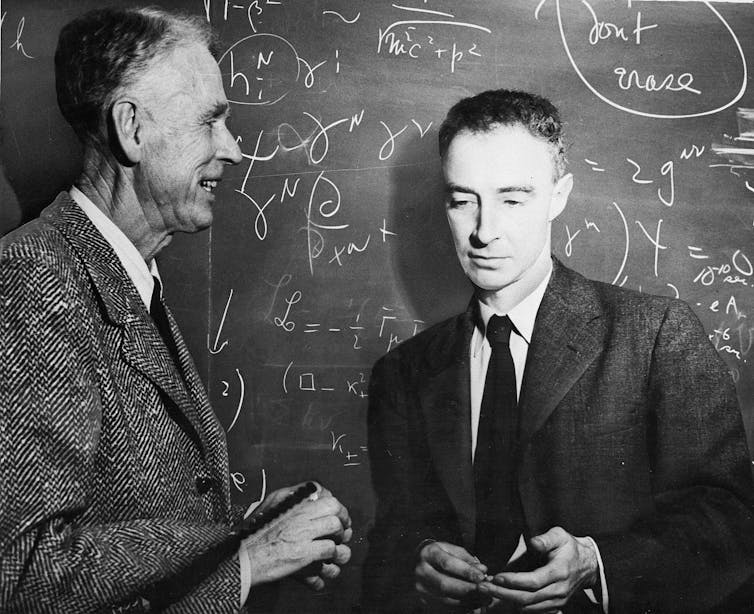

Before developing the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer’s early work revolutionized the field of quantum chemistry – and his theory is still used today

Aaron W. Harrison, Austin College

The release of the film “Oppenheimer,” in July 2023, has renewed interest in the enigmatic scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s life. While Oppenheimer will always be recognized as the father of the atomic bomb, his early contributions to quantum mechanics form the bedrock of modern quantum chemistry. His work still informs how scientists think about the structure of molecules today.

Early on in the film, preeminent scientific figures of the time, including Nobel laureates Werner Heisenberg and Ernest Lawrence, compliment the young Oppenheimer on his groundbreaking work on molecules. As a physical chemist, Oppenheimer’s work on molecular quantum mechanics plays a major role in both my teaching and my research.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation

In 1927, Oppenheimer published a paper called “On the Quantum Theory of Molecules” with his research adviser Max Born. This paper outlined what is commonly referred to as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. While the name credits both Oppenheimer and his adviser, most historians recognize that the theory is mostly Oppenheimer’s work.

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation offers a way to simplify the complex problem of describing molecules at the atomic level.

Imagine you want to calculate the optimum molecular structure, chemical bonding patterns and physical properties of a molecule using quantum mechanics. You would start by defining the position and motion of all the atomic nuclei and electrons and calculating the important charge attractions and repulsions occurring between these particles in the molecule.

Calculating the properties of molecules gets even more complicated at the quantum level, where particles have wavelike properties and scientists can’t pinpoint their exact position. Instead, particles like electrons must be described by a wave function. A wave function describes the electron’s probability of being in a certain region of space. Determining this wave function and the corresponding energies of the molecule is what is known as solving the molecular Schrödinger equation.

Unfortunately, this equation cannot be solved exactly for even the simplest possible molecule, H₂⁺, which consists of three particles: two hydrogen nuclei (or protons) and one electron.

Oppenheimer’s approach provided a means to obtain an approximate solution. He observed that atomic nuclei are significantly heavier than electrons, with a single proton being nearly 2,000 times more massive than an electron. This means nuclei move much slower than electrons, so scientists can think of them as stationary objects while solving the Schrödinger equation solely for the electrons.

This method reduces the complexity of the calculation and enables scientists to determine the molecule’s wave function with relative ease.

This approximation may seem like a minor adjustment, but the Born-Oppenheimer approximation goes far beyond just simplifying quantum mechanics calculations on molecules. It actually shapes how chemists view molecules and chemical reactions.

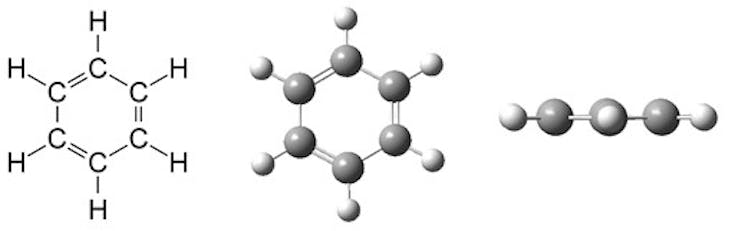

When scientists visualize molecules, we usually think of them as a set of fixed nuclei with shared electrons that move between nuclei.

In chemistry class, students typically build “ball-and-stick” models consisting of rigid nuclei (balls) sharing electrons through a bonding framework (sticks). These models are a direct consequence of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

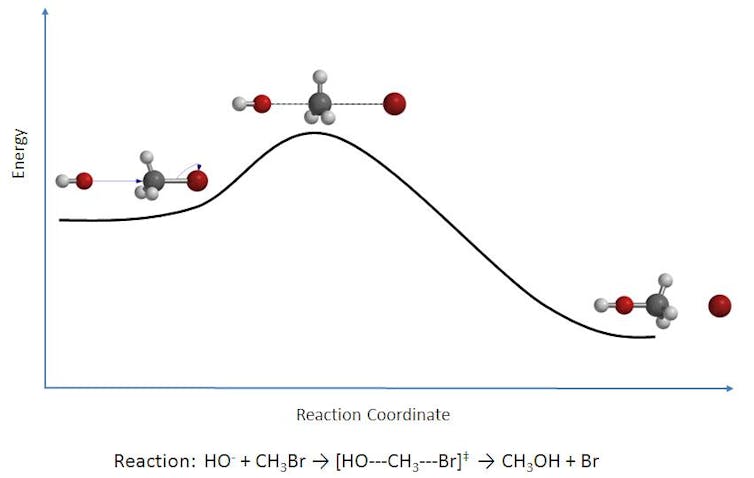

The Born-Oppenheimer approximation also influenced how scientists think about chemical reactions. During a chemical reaction, atomic nuclei are not stationary; they rearrange and move. Electron interactions guide the nuclei’s movements by forming an energy surface, which the nuclei can move on throughout the reaction. In this way, electrons drive the molecule’s progression through a chemical reaction. Oppenheimer demonstrated that the way electrons behave is the essence of chemistry as a science.

Computational quantum chemistry

In the century since the publication of the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, scientists have vastly improved their ability to calculate the chemical structure and reactivity of molecules.

This field, known as computational quantum chemistry, has grown exponentially with the widespread availability of faster, more powerful high-end computational resources. Currently, chemists use computational quantum chemistry for various applications ranging from discovering novel pharmaceuticals to designing better photovoltaics before ever trying to produce them in the lab. At the core of much of this field of research is the Born-Oppenheimer approximation.

Despite its many uses, the Born-Oppenheimer approximation isn’t perfect. For example, the approximation often breaks down in light-driven chemical reactions, such as in the chemical reaction that allows animals to see light. Chemists are investigating workarounds for these cases. Nevertheless, the application of quantum chemistry made possible by the Born-Oppenheimer approximation will continue to expand and improve.

In the future, a new era of quantum computers could make computational quantum chemistry even more robust by performing faster computations on increasingly large molecular systems.

Aaron W. Harrison, Assistant Professor of Chemistry, Austin College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Careless With Words [Comic]

[Source: @bowl_of_beans_]

Science vs. Pseudoscience: 3 Ways to Spot Bad Science

Pseudoscience is composed of a set of theories, methods, and assumptions that may resemble scientific practices but lack genuine scientific validity. In the some of the worst cases, proponents of pseudoscience intentionally exploit this resemblance to deceive and take advantage of people. However, even when well-meaning, pseudoscience can prevent individuals from getting the help they truly need. In this video from Ted-Ed, learn about 3 factors that can help you spot pseudoscience.

Radioactive Dog [Comic]

[Source: @Toothybjcomic]

Are we alone in the universe? 4 essential reads on potential contact with aliens

Mary Magnuson, The Conversation

The House subcommittee on National Security, the Border, and Foreign Affairs met in July 2023 to discuss affairs so foreign that they may not even be of this world. During the meeting, several military officers testified that unidentified anomalous phenomena – the government’s name for UFOs – pose a threat to national security.

Their testimony may have raised eyebrows in the chamber, but there’s still no public physical evidence of extraterrestrial life. In fact, most UFO sightings have earthly explanations, from tricks of the light to weather balloons.

Whether or not these testimonials hold any grains of truth, some scholars argue that simply by listening for signs of extraterrestrials, we’re already engaging in the first phase of contact with alien life.

These four articles from our archives dive into what went down during the subcommittee hearing, why perceived UFO sightings usually have human explanations, and how humanity can learn from history when it comes to engaging with extraterrestrials.

1. Whistleblower allegations

The most interesting testimony of the July 26 subcommittee hearing came from ex-Air Force Intelligence Officer David Grusch, who claimed that the U.S. has nonhuman biological material recovered from a UFO crash site. The Pentagon has denied this claim, and it has denied the existence of any program designed to retrieve and reverse-engineer crashed UFOs.

All witnesses at the hearing advocated for more government transparency around reports of UFOs. Intelligence agencies and the Pentagon currently steward this data, most of which is not public. While having access to more data may help understand what’s going on, as the University of Arizona’s Chris Impey put it, “the gold standard is physical evidence.”

2. Sociological explanations

Again, while no physical evidence has been made public, anyone surfing the internet can see plenty of alleged UFO videos, photos and stories. Barry Markovsky, from the University of South Carolina, is a sociologist of shared beliefs and misconceptions who explained why UFOs seem to captivate the public every few years.

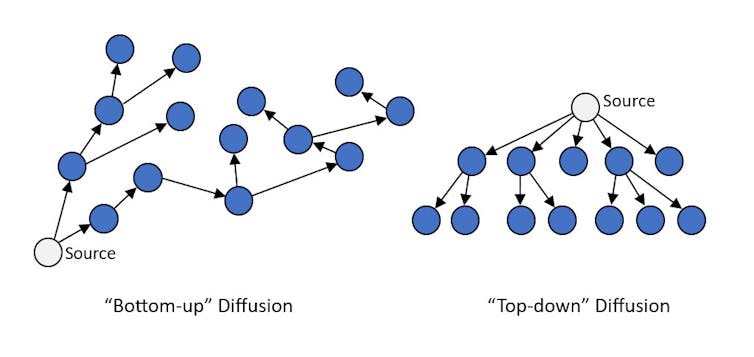

People want explanations for ambiguous situations, and they’re easily influenced by others. Social media enables a concept called bottom-up social diffusion. Say one user posts a blurry video claiming it depicts a UFO. It’s easy for that user’s network to see and repost the video and so on, until it goes viral. Then, when organized institutions like news outlets or government sources publish UFO-related information, that’s called top-down social diffusion.

“Diffusion processes can combine into self-reinforcing loops. Mass media spreads UFO content and piques worldwide interest in UFOs. More people aim their cameras at the skies, creating more opportunities to capture and share odd-looking content,” Markovsky wrote. “Poorly documented UFO pics and videos spread on social media, leading media outlets to grab and republish the most intriguing. Whistleblowers emerge periodically, fanning the flames with claims of secret evidence.”

3. Signature detection

While UFOs might have traction on social media, it’s likely that the first trace of extraterrestrial life won’t come from a crashed alien spaceship. Instead, scientists could potentially pick up signals like radio waves or pollution from some distant galaxy that might indicate extraterrestrial technology.

The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence is a group of scientists all working on the search for extraterrestrial life. Part of what they do is listen for these “technosignatures”.

As two astronomers who work on the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence, Penn State’s Macy Huston and Jason Wright wrote about how humans often unintentionally broadcast signals like radio waves into space. In theory, extraterrestrial civilizations could be doing the same thing – and if scientists can pick up on these signals, they might have their first hints at alien life.

“However, this approach assumes that extraterrestrial civilizations want to communicate with other technologically advanced life,” Huston and Wright explained. “Humans very rarely send targeted signals into space, and some scholars argue that intelligent species may purposefully avoid broadcasting out their locations. This search for signals that no one may be sending is called the SETI Paradox.”

4. Ethical considerations

While the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence hasn’t yet detected any extraterrestrial technosignatures, a working group of interdisciplinary scholars in Indigenous studies argued that the act of listening for these signals may already count as engaging in first contact with extraterrestrial life.

The Indigenous studies working group argued that first contact may not be just one event – rather, you can think of it as a long phase that begins with listening and planning. Listening can be an act of surveillance, and with that comes ethical considerations.

But research groups like the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence don’t often include perspectives from the humanities, even though there are many histories of first contact between groups of people here on Earth to draw from.

James Cook’s 1768 voyage to Oceania, for example, was planned as scientific exploration. But its legacy of genocide still affects the Indigenous people of Australia and New Zealand today.

“The initial domino of a public ET message, or recovered bodies or ships, could initiate cascading events, including military actions, corporate resource mining and perhaps even geopolitical reorganizing,” wrote David Shorter, William Lempert and Kim Tallbear. “No one can know for sure how engagement with extraterrestrials would go, though it’s better to consider cautionary tales from Earth’s own history sooner rather than later.”

Editor’s note: This story is a roundup of articles from The Conversation’s archives.

Mary Magnuson, Assistant Science Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Cunning Cat [Comic]

[Source: @danbydraws]

Anticipation [Comic]

[Source: @adhdinos]

Who God Turns to For Advice? [Comic]

[Source: @theimmortalgrind]