Get ready to groove to the unexpected as DJ Jonny Wilson from Eclectic Method spins the classic sound of a dial-up modem into an electrifying electronic track!

[Via LS]

Get ready to groove to the unexpected as DJ Jonny Wilson from Eclectic Method spins the classic sound of a dial-up modem into an electrifying electronic track!

[Via LS]

I got up this morning, and as I do most mornings, I checked the comments on Geeks are Sexy’s Facebook page to see if everything was ok. What I’m about to show you is probably the most epic online fight I’ve ever seen on my social media profiles.

It all started after posting this comic from @alzwards_corner about putting commercial sauce on a perfectly cooked medium rare steak with a beautiful crust, butter basted with garlic and basil… and then hilarity ensued. First, here’s the comic:

And now for the good part. Please note that both participants have permitted me to republish their discussion.

For today’s edition of “Deal of the Day,” here are some of the best deals we stumbled on while browsing the web this morning! Please note that Geeks are Sexy might get a small commission from qualifying purchases done through our posts. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

–Lego Ideas Tales of The Space Age 21340 Adult Building Set (Build and Display 4 Connectible 3D Postcard Models) – $49.99 $41.47

–Google Pixel Buds PRO Noise Canceling Earbuds – $199.99 $149.99

–Save BIG on Unlocked Google Pixel Phones (Pixel 7, Pixel 8, Pixel Fold)

–HP Pavilion Plus 14 inch Laptop | 2.8K OLED Display | 13th Generation Intel Core i7-1355U | 16 GB RAM | 1 TB SSD | NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2050 Graphics | Windows 11 Pro – $1,299.99 $799.99

–HP 23.8-inch Display Monitor, IPS w/Anti-Glare Full HD 1920×1080 VGA HDMI Edge-to-Edge Screen – $179.99 $129.99

–TeeTurtle – The Original Reversible Octopus Plushie (Angry Blue + Happy Purple) – $15.00 $9.79

–Complete CYBERPUNK Red & Classic RPG Book Megabundle – $259 $18 (and support the Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals charity at the same time!)

–Microsoft Office Professional 2019 for Windows: Lifetime License – $29.97

–Save on Valentine’s Day Favorites (Chocolate, Candy, Cookies, etc.)

–VEWIOR 900W Blender for Shakes and Smoothies – $49.99 $34.98 (Clip Coupon at the Link)

[Source: @salihgonenli]

Exciting news for Sonic fans! Paramount+ has just dropped the official trailer for the highly anticipated Knuckles series. Follow Knuckles (Idris Elba) as he mentors Wade on the ways of the Echidna warrior, set in between SONIC THE HEDGEHOG 2 and 3. Streaming exclusively on Paramount+ from April 26 in the U.S. and Canada.

A fantastic comic by Gavin Aung Than of Zen Pencils inspired by the words of Jacob A. Riis.

Jacob August Riis (May 3, 1849 – May 26, 1914) was a Danish-American social reformer, “muckraking” journalist and social documentary photographer. He is known for using his photographic and journalistic talents to help the impoverished in New York City; those impoverished New Yorkers were the subject of most of his prolific writings and photography. [Wikipedia]

[Source: Zen Pencils | Like “Zen Pencils” on Facebook | Follow “Zen Pencils” on Twitter]

Brace yourselves, Dune fans! The pulse-pounding moment you’ve been waiting for is finally here. Movieclips, in partnership with Fandango and Warner Bros., has just released the electrifying six-minute sandworm-riding scene from Dune: Part Two! Watch Timothée Chalamet’s Paul Atreides as he tame the colossal Shai-Hulud, showcasing his bond with the Fremen culture.

Experience the adrenaline rush before the sequel hits theaters on March 1st!

[Source: @colmscomics]

Julia Wuerz, University of Florida

Have you ever been out on a walk and as you take that next step, you feel the slippery squish of poop under your foot?

It’s not just gross. Beyond the mess and the smell, it’s potentially infectious. That’s why signs reminding pet owners to “curb your dog” and scoop their poop have been joined in some places by posted warnings that pet waste can spread disease.

As a small-animal primary care veterinarian, I deal with the diseases of dog and cat poop on a daily basis. Feces represent potential zoonotic hazards, meaning they can transmit disease from the animals to people.

The reality is that waste left to wash into the soil, whether in a neighborhood, trail or dog park, can spread life-threatening parasites not just among dogs and cats, but also to wild animals and people of all ages. A 2020 study found intestinal parasites in 85% of off-leash dog parks across the United States.

While human diseases caused by soil-transmitted parasites are considered uncommon in the U.S., they infect as many as an estimated billion people worldwide. Signs that remind you to pick up after your pet are not just trying to keep public spaces clean; they’re urging you to help safeguard your community’s health.

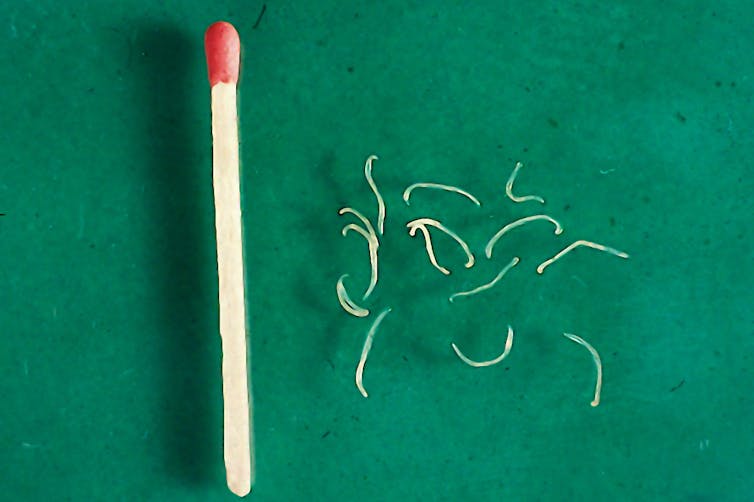

Common dog poop parasites include hookworms, roundworms, coccidia and whipworms. Hookworms and roundworms can thrive in a variety of species, including humans.

Their microscopic larvae can get into your body through small scratches in your skin after contact with contaminated soil or via accidental oral ingestion. Remember that next time you’re outside and wipe sweat from your face with a dirty hand and then lick your lips or take a drink – it’s that simple. After hose or rain water has rinsed contaminated poop into the soil, these parasite eggs can survive and infect for months or years to come.

Once in the human body, both hookworm and roundworm larvae can mature and migrate through the bloodstream into the lungs. From there, coughs help them gain access to the digestive tract of their host, where they leach nutrients by attaching to the intestinal wall. People with healthy immune systems may show no clinical signs of infection, but in sufficient quantities these parasites can lead to anemia and malnourishment. They can even cause an intestinal obstruction which may require surgical intervention, especially in young children.

Additionally, larval stages of roundworms can move into the human eye and, in rare cases, lead to permanent blindness. Hookworms can create a severely itchy condition called cutaneous larva migrans as the larval worm moves just under the skin of its host.

Once the parasite’s life cycle is complete, it may exit the host’s body as an intact adult worm, which looks like a small piece of cooked spaghetti.

Dogs and cats can also develop the same symptoms people do due to parasitic infections. In addition to risks of hookworms and roundworms, pets are also vulnerable to whipworm, giardia and coccidia.

Beyond parasites, unattended poop may also be contaminated with canine or feline viruses, such as parvovirus, distemper virus and canine coronavirus, that can create life-threatening disease in other dogs and cats, especially in adult animals that are unvaccinated and puppies and kittens.

These viruses attack rapidly dividing cells, in particular the intestinal lining and bone marrow, leaving them unable to absorb nutrients appropriately and unable to produce replacement red and white blood cells that help defend against these and other viruses. Vaccination can protect pets.

Many species of local wildlife are within the canid and felid family groups. They, too, are susceptible to many of the same parasites and viruses as pet dogs and cats – while being much less likely to have received the benefit of vaccinations. Coyotes, wolves, foxes, raccoons, minks and bobcats are at risk of contracting parvovirus, coronavirus and distemper.

So, wherever your dog or cat relieves himself – at the park, in the woods, on the sidewalk, or even in your yard – pick up that poop but always avoid contact with your skin. It’s safest to use a shovel to place the poop directly into a plastic bag, or put a baggie over your hand to grab the poop and then pull the plastic bag over it. While it’s tempting to leave the “soft-serve” or watery poops behind, these are often the more likely culprits for spreading diseases.

Tie up the bag and make sure to place it in a trash can – not on top – to avoid inadvertent contamination of a neighbor or sanitation worker. Promptly wash your hands, particularly before touching your face or eating or drinking. Hand sanitizers can take care of many viruses on your skin, but they won’t kill parasite eggs.

Other potential sources of poop – and parasite – exposure are the sandbox, beaches and park sand found under and around playgrounds. Sand is comfortable to lounge on, fun to construct into castles, and softens the impact if you fall off a play structure. But cats and other small mammals love to use it as a litter box since it’s easy to dig and absorbs moisture. Covering sandboxes when not in use and closely monitoring your environment at the beach and playground are key steps toward minimizing the risks of exposure for everyone.

By keeping your pets on regular parasite prevention protocols, with annual testing for intestinal parasites and routine removal of fecal material from the environment, you can help to minimize the potential for these diseases among all the mammals in your environment – human, pet and wild.

Key points to remember to avoid parasites and minimize the impact on your ecosystem:

Julia Wuerz, Clinical Assistant Professor of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

For today’s edition of “Deal of the Day,” here are some of the best deals we stumbled on while browsing the web this morning! Please note that Geeks are Sexy might get a small commission from qualifying purchases done through our posts. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

–All-new Amazon Fire HD 10 tablet – $179.99 $104.99

–HyperX SoloCast USB Condenser Gaming Microphone – $59.99 $42.01

–2-PACK: Blink Mini – Compact indoor plug-in smart security camera – $49.99 $29.99

–Official Creality Ender 3 3D Printer Fully Open Source with Resume Printing Function – $232.48 $169.00

–Amazon Basics Micro SDXC 128GB Memory Card – $17.82 $12.92

–LHKNL Headlamp Flashlight, 1200 Lumen Ultra-Light Bright LED Rechargeable Headlight – $29.99 $15.99

–Ember Temperature Control Smart Mug 2 – $129.95 $103.95

–Complete CYBERPUNK Red & Classic RPG Book Megabundle – $259 $18 (and support the Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals charity at the same time!)

–Microsoft Office Professional 2019 for Windows: Lifetime License – $29.97

–PETLIBRO Automatic Cat Feeder (Battery-Operated with 180-Day Battery Life) – $79.99 $29.99