Jacqui Turner, University of Reading and David Stack, University of Reading

Leisure activities flourished in 19th-century Britain, as legislation was passed limiting the length of the working day and working week, giving people more free time. If you’re struggling to know how to spend your own free time this summer, take a leaf out of the Victorians’ book with these strangely fun leisure pursuits.

1. Read the bumps on your head

Put you hand above your right ear. Do you feel a bump? Then you are clearly selfish! Partly in response to the growth of new cities packed full of strangers, and partly out of a desire to better understand themselves, the Victorians embraced the idea that character could be read from one’s outward appearance, especially one’s skull shape.

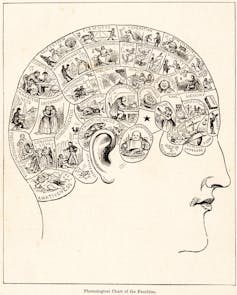

Phrenology was the pseudo-science of reading the bumps on a person’s head to determine their character and potential. Its great populariser was George Combe, whose 1828 book The Constitution of Man was a publishing sensation. Indeed, Combe’s work was so influential that Queen Victoria consulted him to try to understand why her son Bertie (later Edward VII) lacked the intelligence and practical application of his older sister Victoria.

If you want to undertake your own phrenological reading – or, better still, do one for a friend – all you will need are your fingers, a phrenological chart or bust, and a willingness to interpret evidence imaginatively.

If you are in a hurry, you can divide the skull into three. The organs of intelligence are clustered at the front, organs of morality on top, and the animal organs are clustered low down at the back.

According to phrenology, a friend with an unusually high forehead is likely to be intelligent, while one with a particularly thick neck might be best avoided.

This article is part of Quarter Life, a series about issues affecting those of us in our twenties and thirties. From the challenges of beginning a career and taking care of our mental health, to the excitement of starting a family, adopting a pet or just making friends as an adult. The articles in this series explore the questions and bring answers as we navigate this turbulent period of life.

You may be interested in:

How to motivate yourself to learn a language

How you can future-proof your career in the era of AI

Instagram is making you a worse tourist – here’s how to travel respectfully

2. Create a love token

Victorian love tokens came in many varieties. The most common were round, flat discs (often made from smoothed coins), sometimes engraved by hand with names or intertwined initials. You can see a collection of love tokens at the Museum of London.

Love tokens didn’t only celebrate romantic love. Prisoners sentenced to transportation to Australia often made love tokens for those they were forcibly separated from, and London’s The Foundling Museum – built on the site of the Foundling Hospital, which cared for abandoned babies – has a collection of tokens left by heartbroken mothers. These were often humble and tiny, from coins and simple buttons to half a hazelnut shell – but they were symbols of devotion and desperation.

To make the simplest form of love token, you will need a coin, a hammer and a vice. Put the coin in the vice, leaving about one third on view, and hit it with the hammer. Once it has bent, flip the coin over, leaving the unbent third showing, and now hit that with the hammer. Done! You have a gift for your loved one to cherish.

3. Kick someone’s shins (gently)

If you enjoyed striking the coin or discovered a highly developed organ of combativeness during your phrenological examination, you might also want to try England’s oldest martial art – shin-kicking.

The roots of this strangely violent sport are believed to lie with Cornish miners in the 17th century, but in the 19th century it became popular in Lancashire mill towns, where it was known as clog fighting or “purring”.

Participants would don shepherds’ smocks, hold each other by the shoulders, and take turns to connect their foot with their opponent’s shin. The contest is won when one competitor cries “sufficient”, to indicate that they have had enough of being kicked. If you fancy trying this daring sport for yourself, soft shoes and padding stuffed into your trouser legs are recommended.

4. Make a stereoscopic image

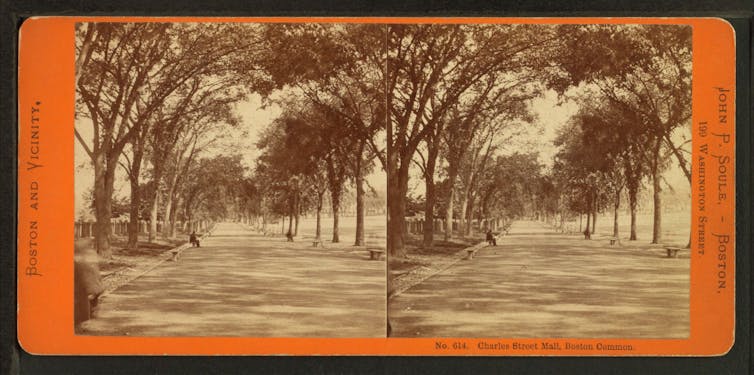

It’s well known that the Victorians pioneered photography, but less so that they also invented 3D technology. Stereoscopy – a technique that creates the illusion of depth in a two-dimensional image – was discovered by inventor Charles Wheatstone in 1832.

Stereoscopic image cards of landscapes, buildings and portraits were fashionable throughout the 19th century, and you too can easily make your own stereoscopic images.

What Wheatstone realised is that our sense of depth is created by the distance between the pupils of our left and right eyes. Each sees a slightly different image, which our brain then aligns. To create this stereoscopic effect artificially, take two photographs of the same object from very slightly different positions, place them side by side, and then look at them cross-eyed.

This cross-eyed viewing can be achieved with practice, but many middle-class Victorian homes had stereoscopic viewers, which worked in the same way as the View-Master toy that was popular in the 1970s.

5. Try gurning

Finally, gurning is the practice of deliberately distorting your facial expression by projecting your lower jaw forward and up.

In the tradition, which dates back to at least the 13th-century,

gurners frame their face inside a horse collar. The current home of the Gurning World Championships, Egremont Crab Fair in Cumbria, has been running since 1267. It returns this year to much fanfare, after a three-year hiatus due to the COVID pandemic.

While anyone can try gurning, you might be ill-advised to do it when also presenting your love token.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Jacqui Turner, Associate Professor in Modern History, University of Reading and David Stack, Professor of history, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.