Researchers at Harvard and Northeastern say Google’s Flu Trends service, which tries to predict flu outbreaks based on search activity, has become less reliable over time. They say the effects of even small changes such as those to Google’s own autosuggest tool may have been allowed to mount up and call it a lesson for using “big data.”

The logic behind Google Flu Trends, which dates back to 2008, is simple enough: the sheer number of people making Google searches means that as an outbreak begins in a particular area, the number of searches relating to relevant symptoms measurably increases. In turn Google may be able to predict increases in cases of flu before the numbers of diagnosed cases reflect that increase.

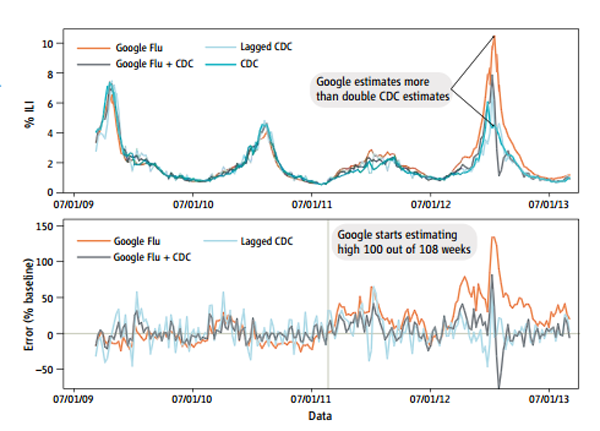

According to the Harvard and Northeastern research, published in Science, the Google predictions have been getting increasingly less accurate. It says that in a 108 week period between August 2011 and September 2013, Google’s predictions for the US proved markedly higher than the real figures in 100 weeks. (Pictured – credit Harvard University.)

The researchers dismiss one possible explanation, which is that media-fuelled panics caused people who didn’t have flu to make searches online. Instead they note another possibility: that Google has updated its autosuggestions and search results rankings so that people who search for symptoms such as “fever” or “cough” are more likely to see, and go on to select, options to search for flu-related terms such as distinguishing a cold from the flu.

According to the researchers, Google’s use of other people’s search activity to make suggestions may exaggerate the problem with a snowball effect: the more people search for flu-related terms, the more people are given the suggestion to search for flu-related terms. That could mean that while the basic direction of Google Flu Trends mirrors reality, the scale of the trend movements is overblown.

The paper draws two main conclusions. The first is that the problems highlight what the researchers call “big data hubris”, the mistaken belief that simply increasing the quantity of data collected for analysis is enough to improve results even without also working on the quality of analysis.

The second is a criticism of Google keeping so much of the detail of both its methodology and the data secret, even in aggregated form. According to the researchers, Google making more information available would benefit society:

Google is a business, but it also holds in trust data on the desires, thoughts, and the connections of humanity. Making money “without doing evil” (paraphrasing Google’s motto) is not enough when it is feasible to do so much good.