Researchers have used brain scans of one monkey to control the movement of another monkey. It’s a first step in a complex road towards helping paralysed people regain some movement control.

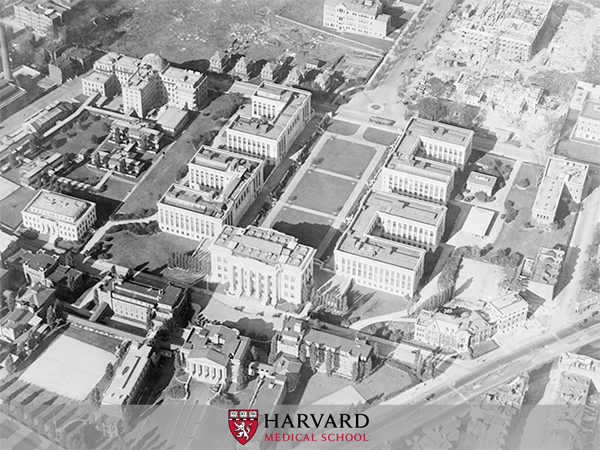

The research from Harvard Medical School (carried out at Massachusetts General Hospital) is detailed in a paper titled “A cortical–spinal prosthesis for targeted limb movement in paralysed primate avatars”, published in Nature.

The idea of the research was to track the brain activity during movement, isolate key movements, then “translate” it into electrical stimulation to the spine. This involved implanting a chip in a “master” monkey’s brain to monitor 100 neurons and then putting it through a training process to match neuron activity to movements.

The researchers then implanted 36 electrodes into an “avatar” monkey which had been sedated, used as an ethical way of simulating paralysis. They were able to take the patterns of activity when the master monkey moved and figure out the electrode combination required to stimulate the same activity on the avatar monkey.

They then tested the system in real time using a crude video game. The master monkey saw a cursor and a target on a screen. The avatar monkey, which was in a separate room, controlled the cursor with the joystick. Every time the cursor hit the target, the master monkey got a juice drink as a reward.

Once the master monkey figured out that just thinking about moving the cursor somehow made it move, the avatar monkey moved the joystick correctly almost every time. The researchers repeated the experiment with the same monkeys but reversing their roles, with similar results: a 98 percent success rate.

At this stage the experiment is purely a proof of concept. The long-term aim is to use a similar technique on paralyzed humans. In that case, the human’s brain would be translated into electrical impulses on their own spinal cord.

That brings about several major challenges. It’s likely to be extremely challenging to advance the level of control from pushing a joystick back and forth to a level of movement and control that has practical uses such as gripping or lifting.

There’s also a big difference between muscles in a sedated and paralyzed person: with the latter, muscles get more rigid and thus harder to control even with stimulation.