NASA has officially confirmed that Voyager 1 has left our solar system.

The announcement comes to coincide with the publish of a paper in Science with the understated title “In Situ Observations of Interstellar Plasma With Voyager 1.”

The paper details “strong evidence that Voyager 1 has crossed the heliopause into the nearby interstellar plasma.”

Even that wording is perhaps understated. What has happened is no less dramatic than this: a man-made object has now traveled so far (around 12 billion miles) that it is no longer significantly affected by our sun: it now lies in the space between the stars.

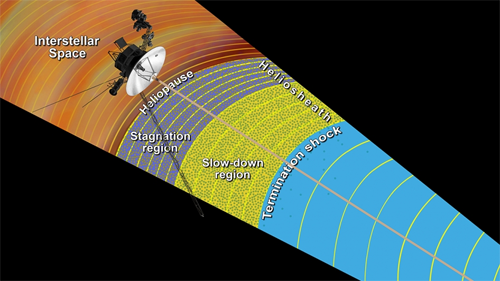

We’ve covered Voyager’s final-stage travels over the past few years at GAS. Back in 2010 it entered the heliosphere, which is the part of our solar system that lies beyond the range of any planets. It then passed into the heliosheath, the point at which solar winds slow down because they are being affected by the interstellar medium, which is what lies outside solar systems.

Research published in March showed that by 25 August last year, Voyager had crossed the heliocliff. That’s the point at which the interstellar medium (“the outside”) has a greater effect than our solar system (“the inside”.)

That only left the final border, the heliopause, which is the outer extremity of the sun’s influence and the formal start of the interstellar medium itself. NASA has now completed the analysis of the data that prompted the March report, noting that “We have been cautious because we’re dealing with one of the most important milestones in the history of exploration. Only now do we have the data — and the analysis — we needed.”

That data is based mainly on both the levels and movement of direction of plasma surrounding Voyager. The analysis formally confirms that by 25 August Voyager had not only passed the heliocliff, but also the heliopause. Although it’s not possible to put a precise date on the moment Voyager left the solar system for good, as it may have hovered back and forth, the data suggests it first touched the edge on 28 July. It’s around two years earlier than some predictions.

The breakthrough came almost 35 years after Voyager’s launch on 5 September 1977 (ironically a couple of weeks after a sister craft, Voyager 2.) It was initially designed to explore Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, taking account of a rare alignment of their orbits.

It will now travel unrestricted for another 40,000 years or so before coming close to another star’s solar system. Unfortunately we’ll almost certainly never know if that happens as the craft’s instruments and transmitters are powered by a plutonium source which is expected to run out in a decade or so for now.

The only possible exception to this, of course, is if extraterrestrial life does exist and can make sense of the Golden Record, a phonograph record with accompanying stylus that contains sounds of greetings in 56 languages, animal noises, and pictures of human culture and the natural world.

It seems an unlikely quirk of fate that this should happen, but coincidences are possible, as shown in this screen shot of the sight that greeted me today when I checked back on out previous stories on Voyager and discovered this intriguing placement of an overlaid advertisement:

(Top image credit: NASA)