Smartphone displays may now be good enough to allow ophthalmologists to diagnose patients even when they are away from their base hospital. But there does seem to be a major limitation in the research that means some conclusions offered by third parties might not be quite as they seem.

There have been suggestions in response to the research that it could be possible for emergency room staff to take a photo of a patient’s eye on a smartphone, transmit it to a remote specialist, and await a diagnosis. That could be useful for ER departments that don’t always have an ophthalmologist on hand.

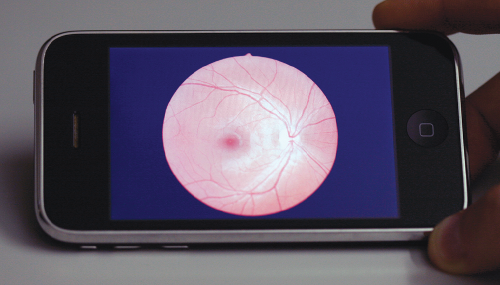

The problem is that in effect the study, carried out at Emory University in Atlanta, simply examined the quality of the display on the iPhone, not the phone camera itself. (Sadly it was the 3G model, meaning no room for gags about the retina display.)

Dr Valerie Biousse and colleagues used ocular cameras to take photos of the interior of the eyes of 350 patients who had reported problems potentially related to the eye. They then asked two ophthalmologists to examine the pictures on a “typical” desktop computer, rating the quality from one to five. They were then asked to do the same task six weeks later with a random selection of 100 of the images, this time displayed on an iPhone 3G.

One ophthalmologist said the desktop photo was better quality in one case, the two were equally good in 53 cases, and the iPhone photo superior in 46 cases. The other ophthalmologist favored the desktop image twice, rated them equally 56 times and preferred the iPhone picture 42 times.

The researchers concluded that they believed this was “because the advantages of the iPhone’s display (eg, higher dot pitch and brightness) outweighed its disadvantages (eg, lower resolution and smaller screen area).

There are some clear limitations here, and not just the limited scope of what was being examined. We don’t know the quality of the display on the desktop monitor — an opthalmologist who expects to get a lot of images sent for remote diagnosis would surely invest in a high-resolution screen.

We also only know which pictures the opthalmologist preferred. While the answer may well be the same in most cases, the study didn’t try to find out which photos allowed the most accurate diagnosis.

But the biggest limitation is that this only covers one side of the story. The study was in no way trying to look at the quality of pictures taken on a smartphone camera rather than professional medical equipment. It also didn’t examine the practicalities of transferring an image from an ocular camera to a smartphone or computer for transmission to the opthalmologist’s phone.