Researchers at UC Berkeley have shown its possible to decipher the words that a brain is thinking about. That could theoretically make it possible for a patient in a coma to communicate, though that’s a long way off.

The research follows previous studies into the physical effects of thought. It had already been shown that the pattern of blood flow in the brain can be matched to the images that people were thinking about, albeit in a fairly imprecise manner.

The new study aimed to take that a step further by looking for specific words. Dr Brian Pasley’s team looked at the superior temporal gyrus, which is a part of the brain that is linked to hearing and helps “translate” the sound of a word to its meaning.

The team carried out the study on patients undergoing treatment for epilepsy or brain tumors. While that may not be a perfect control group, it did mean there was less disruption in the testing, which involved attaching electrodes to the brain.

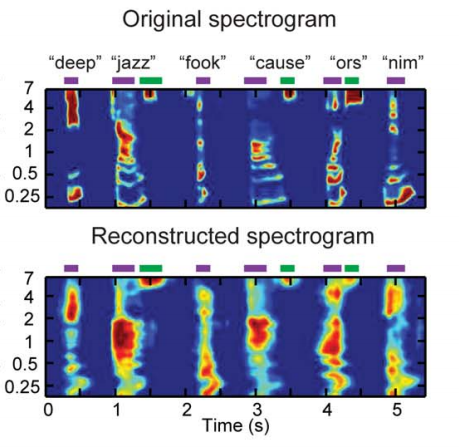

Firstly the researchers played recordings of a series of words, both genuine and made-up (though people in the north-west of England would take issue with “fook” being fictional) to the patients, then built up a spectogram image of their brain activity. They then asked the patients to think about the words, such that they would “hear” the word in their internal monologue, with the researchers again measuring the brain activity.

Rather than simply compare the visual recordings of the activity, the researchers also developed a computer system that could turn the recorded thoughts into simulated speech. In most cases the speech resembled the original word but sounded like a voice distorted by echoes and other interference. It was close enough that the researchers could correctly identify the word being “spoken” in 90 percent of cases.

Pasley believes the technique could go beyond simply working with a controlled range of possible words. He says it’s possible to build up a reference list of phonemes, the smallest distinct sound that goes towards making speech, and thus piece “thought” words together. Pasley likens it to the way an expert pianist knows what sound each key makes and can therefore work out what tune is being played without hearing it, just by seeing the keys being pressed.

Whether this really could be used for patients who are totally unable to communicate, such as those in comas, remains to be seen. Despite the results of this test, it’s still possible that although the same areas of the brain are working both when somebody imagines a sound and when they really hear it, the process may be different.