By Jimmy Rogers (@me)

Contributing Writer, [GAS]

About a week ago, my mother (who is a nurse) asked me, “What can I tell my patients to make them understand why a live virus vaccine isn’t scary just because it’s alive?” I answered her question to the best of my knowledge, but it got me thinking about how little the average person knows in regards to vaccines.

To the layman, a vaccine is essentially some kind of representation of a disease that allows the immune system to get a head start on protecting you. In fact some people probably don’t even know that! While the above is not wrong, I think making an informed decision is always preferable to blindly trusting the magic of science. Read on if you agree!

Who Are We Dealing With?

Keep in mind that this is an enormous oversimplification of the process. Most pathogens are prevented from even gaining a foothold by your innate immune system, which uses non-specific measure like your skin and mucus membranes. Only once your innate side has essentially lost ground does your adaptive immune system become activated and being to tune itself to specific antigens.

Intro to Vaccines

Where do vaccines come into all of this? Well, scientists have determined that the second, faster response to an antigen can be primed by fooling the immune system a little bit. If it’s flu season, for instance, it’s a good bet that a lot of people will contract a certain kind of influenza. Vaccine makers can add examples of the strain(s) of influenza they expect to that season’s flu vaccine and distribute it to a large number of people. The people who get the shot will have a very mild response to the vaccine flu (because the immune system easily defeats it) and their bodies will now be prepared in the event of a “real” infection out in the wild.

Another benefit to the vaccine method is an idea called “herd immunity.” If you vaccinate 80 percent of a herd of cows against a disease, you will be preventing most of them from becoming infected and consequently spreading the disease. As an added bonus, the 20 percent without the vaccine are much less likely to run into it either. This is because many diseases are spread from individual to individual and by breaking the links in the infection chain, the disease will spread much slower in a population. This works as well as in cows as it does in people!

Types of Vaccines

The first and simplest way to trigger a protective response is to give a patient a dose of either a weakened or killed bacterium (or virus). Weakening, also known as attenuating, can be accomplished by growing the pathogen in either a strange environment, such as an abnormally low temperature, or in a non-human host, such as a rabbit or a guinea pig. Killing is usually done with either a chemical or a temperature that is lethal to the pathogen. One downside to the latter approach is that the all-important antigen recognition sites on that pathogen (called “epitopes” by immunologists) can change and misinform the immune system, leading to an ineffective vaccine.

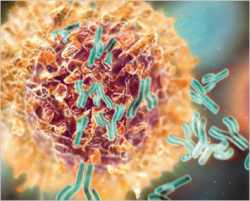

Most of the vaccines you take during your life will fall into the above categories: live attenuated or killed. Some, though, go about things differently. Subunit vaccines, for instance, use only the parts of the pathogen most easily recognized by the immune system. While this may seem like a much smarter idea, these vaccines are not as common because they can be complicated to produce effectively and they expose the immune system to far fewer antigens than whole cells.

One vaccine you may have taken that does not use whole cells is the tetanus vaccine. The bacterium that causes tetanus, Clostridium tetani, is relatively harmless to humans. It produces a toxin, though, that can result in lockjaw. The vaccine uses inactivated forms of the tetanus toxin, instead of the bacteria itself, to help your body recognize and neutralize the functional toxin before it can do any damage.

For more info on the different types of vaccines, I suggest the NIAID/NIH page.

Potential Danger of Vaccines

Those are the primary types of vaccines you will probably encounter today. There are a number of new strategies being developed, but for the sake of time, I’ll finish up with a word of caution. Vaccines, by and large, are a very safe technology. Billions of people have used them for many many years now and there is a great deal of oversight in their creation. That being said, there are ALWAYS risks with any medicine and vaccines are no exception.

First and foremost, live vaccines can, in rare instances, “revert” into a virulent form of the disease. The Sabin polio vaccine (a live attenuated vaccine) has been known to do this and is, for that reason, only used in high risk areas. It is much more effective than the Salk killed virus vaccine, so in some parts of the world the benefits outweigh the risks.

Also, some people have negative reactions to the ingredients in some vaccine. Whether it’s a high sensitivity to the antigens themselves or an overreaction to the adjuvants (immunization enhancers required for many vaccines to function), there will always be a small number of patients with adverse side effects. If you want to know more about a specific vaccine, ask for an information sheet from the clinic or hospital detailing the type of vaccine and any prominent risks. Just don’t expect technical specs like it’s a piece of software.

In the end, you have to weigh your options just like anything else. The odds are relatively low that you’ll get more than a little sore in the arm from your flu shot. The FDA (which sets the standard in most of the world for vaccine oversight) keeps a very close eye on new vaccines and requires that any with abnormally high instances of side effects be recalled and reviewed. As a relatively well educated microbiology student, I feel safe and comfortable taking vaccines to protect me from anything I might be at risk of contracting.

What do you think? Are you planning to get your flu shot(s)? Have you already done so? Any other questions about vaccines? If so, please post them in the comments and I’ll try to answer your questions. Also, you can @ me on Twitter!

[Antibody image from The NY Times and MabThera Virtual Press Office | Vaccination image from MSNBC-Health | Header picture: Flickr (CC)]